Legal liability

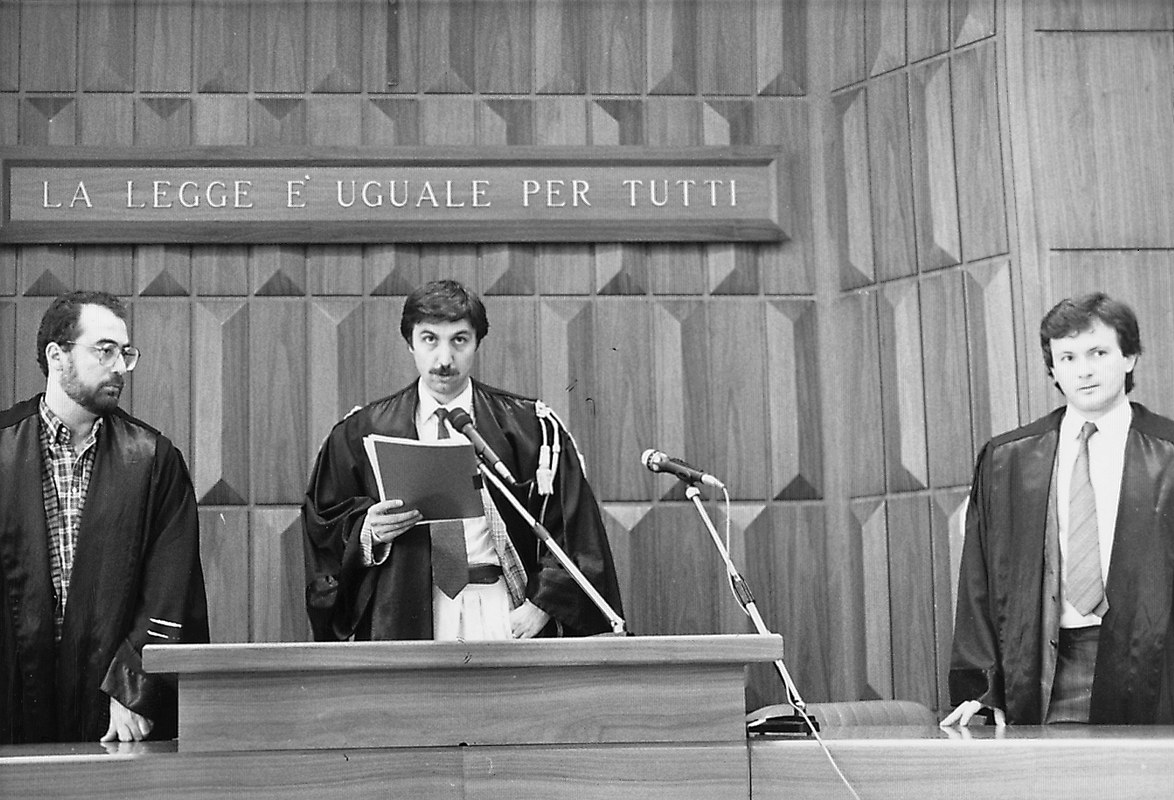

The first trial took place in Trento and was concluded in less than three years. Legal proceedings ended after another four levels of judgment with the second sentence pronounced by the Supreme Court, which was delivered on 22nd June 1992. This verdict confirmed the sentences passed by the first trial. 10 people were convicted of multiple manslaughter and culpable catastrophe, in other words:

- Those responsible for building and managing the upper basin which first collapsed: the managers of the mine and some officials from companies involved in building and developing the upper basin from 1969 to 1985.

- Those responsible from the Mining District of the Autonomous Province of Trento who failed to carry out checks on the tailings dams.

Nevertheless, the prison sentences were eventually remitted and none of the persons sentenced was actually sent to prison.

The following parties, since they were regarded liable owing to the conduct of their employees, were ordered to liquidate damages:

- Companies licensed to operate in the Prestavèl mine during the same period, or companies involved in decisions concerning the tailings dams: Montedison JSC, Industria marmi e graniti Imeg JSC on behalf of Fluormine JSC, Snam JSC on behalf of Solmine JSC, Prealpi Mineraria JSC.

- The Autonomous Province of Trento.

Compensation for damages of over 132 million Euros was almost completely allocated to 739 plaintiffs in 2004 by Edison on behalf of Montedison (31%), Eni Snam on behalf of Solmine (26%), Finimeg on behalf of Imeg, Fluormine (16%) and the Trento Autonomous Province (27%). Prealpi Mineraria, which in the meantime had gone bankrupt, never allocated any sum of money to the damaged people.

Compensation for the loss of human lives was quantified as for road accidents. Following the transaction, the sums forwarded by the State and the Trento Autonomous Province for rescue operations, rehabilitation and reconstruction were fully reimbursed.

Besides the actions and omissions considered relevant from a criminal point of view, the Stava Valley disaster was also caused by behaviour transcending the legal dimension.

For instance, there were decisions by the licensed companies and public bodies entrusted with safeguarding the territory and the safety of the people which favoured economic profits instead.

Apart from significant criminal liabilities and omissions, the Stava disaster was caused by a concurrence of actions which go beyond the judicial sphere and which are mainly characterised by having put economic profit before the safety of third parties.

The conduct of numerous Public Offices and of the constructors and managers of the lower basin was not considered significant from the criminal viewpoint by the judges, although this conduct was severely censured.

Nor was the conduct of public administrators and managers of the concessionary companies considered significant from the criminal viewpoint because they entrusted the technical aspects to employees who should have had adequate knowledge and expertise. These persons entrusted the relevant administrative offices with the analysis of the technical aspects, since technicians provided with adequate competence worked in these offices.