Slimes nightmare enrages community

Date : 1995-12-01

Bronwen Jones

TEARS and righteousness make a potent mix in an angry young woman out to fight the wealth and might of big industry. Sitting atop a crumbledown dam looking over her community, RenŽe Smith, 21, adjusts blue rimmed spectacles and says: “We will not let them build their dam on our doorsteps. We will not let Merriespruit happen twice.”

Working for a firm of engineering consultants, she has a better than average understanding of plans to construct a R16,8-million slimes dam at Fleurhof, in apparent disregard for those interred in the mud of Merriespruit and in the Bafokeng disaster 20 years earlier.

Rand Mines Properties (RMP) wants to clear 50 mine dumps around Johannesburg, reclaiming the gold and making industrial land available for building. To do so, it must dump the dirt at Fleurhof.

Smith says: “The Merriespruit court case is still pending and yet they expect us to happily accept Fraser Alexander, the same firm of engineers.” She is angry at what she feels is RMP’s and the Minister for Mineral and Energy Affairs’ placing of the economy and the country first. “They are so convinced of their own importance they have forgotten we are important too.

“It may not have been me who bought a house in Fleurhof, but my parents did. They have been building up a legacy for me and my brother. Now it is worth nothing. Yesterday an estate agent told me, ‘Fleurhof is a dead zone’.”

The community is united in its opposition to the new dam, with each of the 450 households signing the petition delivered to Pik Botha, Minister for Mineral and Energy Affairs. They have a fighting fund and a committee fast getting a grip on environmental impact assessments and the finer points of dam building. They have employed a separate firm of consultants to independently assess the dangers of the massive structure.

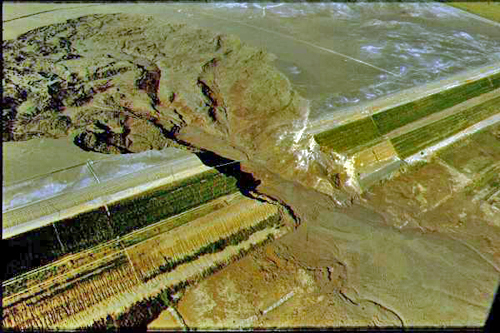

While there are dumps nearby, they are a dusty irritation, not a looming menace, and were there before Fleurhof. RMP’s plan is to merge a group of tumble down dumps not used in decades into one mega-dump. Again breaching engineering wisdom, it will place new material on an old structure. It will dump and process 24 hours a day, 324 days a year, for the next 12 to 15 years.

Slimes dams are not walled in by concrete. They have vast banks of earth and sand holding back a porridge of fine industrial waste. A porridge that, once it flows, is unstoppable.

Every year, on average, there are two slimes dams failures in South Africa. The year that they started to build the dams at Merriespruit, there was a major failure at Impala Platinum Mines, known as the Bafokeng disaster. The slimes poured into a mine shaft, killing the men below, and flowed on the surface for 25 kilometres.

Fleurhof is, at best, 300 metres from the site of the intended mega-dam. While RMP promises daily, weekly and monthly checks, there is always the possibility of human error.

In February last year, when the Merriespruit slimes dam burst, 17 people died and some who survived live lives of indescribable misery. The trial of officials for culpable homicide starts in March.

Community leader Eugene Marais says: “It’s an accident waiting to happen. We will not let it be

The old slimes dams at Fleurhof were used in the 1920s. The community itself was not established until around 1974.

Fleurhof was established as a white community but, with Soweto too close for comfort after the 1976 uprising, residents fled. Indians turned the township down. But coloureds, used to being betwixt and between, moved in gladly.

“There is nothing you can say to convince someone who is frightened,” says Dick Plaistowe, director of RMP’s land clearing and gold recovery division. He is aggrieved that Fleurhof is attracting attention, and says RMP has had to produce a R28 000 video to explain how benign the scheme is, as well as spending tens of thousands of rands on models, brochures, consultations and helicopter trips for various committees.

Plaistowe argues the dumping ground is essential for RMP to continue to employ 620 people. But Fleurhof residents would sell their homes to RMP if they could. While Plaistowe insists the development will not cause property prices to drop, he says RMP doesn’t want to buy the houses in Fleurhof, valued at R81-million. He says the company has no choice over its dumping ground. The gold processing is so marginal that it is not economic to take the debris further afield.

Work was due to start on the mega-dump last month, but has been delayed by the residents’ protests.

“With the extraordinary safety measures being taken, living next to the dam is the same risk as living normal daily life.”

Marais says this is illogical, and if the dam fails, he believes RMP is underinsured, with only R3,5-million in its mine closure fund at the moment.”There are already miners’ graves on top of the dam. We don’t want a mass grave at its side.”

The shadow of Merriespruit lies long on the ground of Fleurhof. Divided by a distance of several hundred kilometres, the living of one community and the dead of the other seem melded in their fear of what lies ahead: fear of the mud.

Clever new ways to blow things up and more

Date:02 Feb 1996

Bronwyn Jones finds more brilliant and bizarre inventions in her monthly look through the Patents Journal

DON’T let the thousands of expected redundancies at Anglo American’s Freegold fool you; if the Patents Journal is anything to go by, South African mining is going from strength to strength. There are 15 major new mining patents this month alone, from automated drilling machines to pneumatic hammers, rock anchors and plastic rings that protect mine props (though not necessarily the men working between them). The Americans, Austrians, Germans and Danes are all eyeing the mining industry for its healthy profit potential, and the metallurgists looking at Columbus Stainless Steel and beyond, have deposited detailed documents on gold treatment as well as a series of new wonder alloys and steels. New air cooling systems take account of the ban on those dangerous CFCs, and there are a stack of clever ways to blow things up. Would-be terrorists or industrialists should visit the patent office for details. Low-cost housing ideas continue to abound, from bricks for idiots to Louis le Roux Benade’s plaster-your-own inflatable igloos. Wave Paper’s answer to South Africa’s housing problems is a wooden panel filled with corrugated cardboard. To help mass housing projects cut costs, Duncan McGregor has designed a bath and basin that can be served by a single pair of hot and cold water taps. Economy is wonderful, but would McGregor choose to follow his suggestion that `it may further comprise a kitchen sink adjacent (to) the bath’? Then again, no one ever said an inventor had to care about building regulations or hygiene. Sport always appeals to the inventive mind. While some concentrate on new dimple patterns for golf balls, Johann Stassen has devised a method of manufacturing a playing ball with a laterally biased flight path … sounds a little like cheating to me. American Ying-Lang Lin has turned to another of our favourite pursuits: driving. He has a rather natty car safety wheel with a spare tyre inside it.

Unilever has patented a toothbrush on legs and Chyn-Herng Hwu has found a way to walk on water. His `floaters’ look like skis but have a little paddle hanging down below; if you walk you move forward. Willem Kuperus was obviously feeling pretty pessimistic when he invented his tug-along rubbish bin, designed so householders can take their own waste to the refuse site. The Atomic Energy Corporation hasn’t announced any plans for new nuclear sites, yet Frenchman Christian Valason has patented his steam generator for nuclear power stations here, and British Nuclear Fuels has patented processes for treating contaminated land and contaminated materials. Continuing with pollutants, Imperial Tobacco has patented a cigarette that includes a tube of sticky liquid in the middle. Werner Kaufman will save us from the dangers of the sun by producing protection factor clothes, rated like sun creams and treated with fluorescent compounds. And then there’s a whole tumble of trademarks. There are a few that one can’t imagine anyone else wanting to use anyway. Who, after all, would want to mark clothing, footwear or headgear with the Vaal Reefs logo? Then again, OJ Simpson T-shirts did rather well. Maybe there could be a whole new line in Merriespruit mittens and Harmony hats?

Criticism not necessarily media-bashing ONE read your editorial `Third Force, Fourth Estate’ (M&G January 26 to February 1) as with other Mail & Guardian editorials — with much interest. Regardless of whether one agrees with the opinions of your editor(s), the M&G has had a distinguished record of principled defence of human rights and media freedoms, in particular. It is this tradition that it seeks to maintain in this

However, an unfortunate mindset creeps into the logic of the editorial, undermining rational debate of what is indeed a critical question for South African society, whichever estate its various sectors may belong to. This is captured in the very first phrase: `In the dangerous game of media-bashing …’ Thus, the very first assumption is that President Nelson Mandela was merely engaging in media-bashing when he raised the question about weaknesses of the South African media, both print and electronic, regarding the erstwhile debate on the Third Force. >From such a premise, it is understandable, but not justifiable, that the editor summons arguments in collective defence of the media. What results from this is a narrow estate patriotism: `Our estate, right or wrong!’ Dare South Africa forget that the assertions by the African National Congress and others regarding the Third Force were laughed out of court in most of the local media — and the most influential ones at that — in the early 1990s! The fact that an example of the exception, in this instance, was given as John Carlin and not Kit Katzin, Phillip van Niekerk or anyone else should not be used to detract from the president’s observation. And it is an observation that the Fourth Estate should take seriously. In my view, the main trends then, on the Third Force debate, should even feature in the training of cadet journalists in our country and further afield, if only as an experience not to be repeated. The situation in South Africa has changed. And the M&G can now evince some zeal in defence of the practices of the estate as a whole and in a show of South African patriotism. Perhaps, in this new situation, the M&G and the handful of journalists in Vrye Weekblad, The Star and others who sought to get to the root of the Third Force allegations are no longer the exception to the rule. Perhaps they are now in the majority and are quite influential in the media establishment. The M&G, Vrye Weekblad and the other brave journalists who did all this should indeed be applauded. But it would be a mighty error, both for historical record and the future development of journalism, to come out in defence of all Fourth Estaters on this and other specific debates. It is a disservice to an exceptional corps of journalists who endeavoured to do their work, without fear or favour, when it was less fashionable and even a matter of life and death to do so. In the search for the truth (and reconciliation), the Fourth Estate is not immune to critical examination! — Joel Netshitenzhe, director of communication, Office of the President

English will look after itself GJ Vroom (Letters, M&G January 26 to February 1) argues that since most of the world’s languages are expected to die in the next century, we might as well leave for dead all but a couple of South Africa’s official languages (reserving a special place for English). However, Vroom’s argument is based upon the misapprehension and misuse of data relating to language death. While Vroom is correct that most of the world’s languages are expected to be dead in the next century, none of the official languages of South Africa is at particular risk. The languages expected to die are mostly among the majority of the world’s languages that have fewer than 10 000 speakers. The least widely spoken of the official languages, Venda, is estimated to have 170 000 speakers. By contrast, countries like Nigeria, with hundreds of local languages, will probably undergo extreme linguistic

The estimates of language morbidity assume that the status quo will continue, that minority languages will continue to suffer social and economic devaluation from both within and without the minority communities. Michael Krauss’s morbidity predictions (cited by Vroom) were not intended as simple fact, but as a call to action to prevent the loss of languages in the coming century. Just as species can be returned from the brink of extinction through protective measures, so can a moribund language be returned to vitality, as has been demonstrated by language preservation efforts in Ireland and Native America. For a language to die is for a culture to die — genocide without corpses. The way to prevent language death is to encourage cultural pride (not to be confused with ethnocentrism), reflected in use of the language at home, in literature, and in other local forums. This can be done while maintaining English as a lingua franca. Native English speakers world-wide are peculiarly monolingual, and thus tend to see other languages as competitors for linguistic dominance. But the rest of the world lives multilingually — there is no reason to believe that support for other languages will in any way prevent people from using English in appropriate situations. Finally, Vroom argues that South Africa should follow the United States in accepting its own variety of English as a lingua franca. It is important to note, however, that the US has no official language and does little to regulate language use. (Attempts to make English an official language in certain states and cities have been deemed unconstitutional.) The place of English in America has evolved, it has not been decreed. Market forces, not official policy, are responsible for the current success of English. — M Lynne Murphy, Department of Linguistics, Wits University

New myths for old IN deconstructing Livingstone’s career as `an imperial myth’ (`Doctored Livingstone’, Review Books January 19 to 25), it appears that Timothy Holmes, as amplified by Stephen Gray, has constructed a few myths of his own. The suggestion that the great Kwena ruler Sechele I (who was hardly `old’ at the time of his August 1848 baptism) ate his wives, is the sort of racist nonsense that went out of fashion with Tarzan movies. While the Tswana verb `go ja’ can mean `to copulate’ as well as `eat’, Sechele’s greatest culinary sin was to spend much of his treasury importing such exotic items as curry powder, tea and Worcestershire sauce for his chandeliered dining room. The notion that Sechele, who was Livingstone’s best-known but not only convert, returned to polygamy is also misleading, though at least rooted in the well-known incident of his dalliance with former and, according to most Tswana sources favourite, ex-wife Mokgonong (in addition to countless literary references, the affair was the subject of a West End play). Mokgonong subsequently remarried and lived to see many grandchildren. Earlier, the Kwena women had downed their hoes to assure that proper provision was made for her and the two other former wives, Motshipi and Modiagape. Until her death, Sechele remained monogamous with his chosen queen, Selemeng. In settler history, Sechele is best forgotten as the leader of pan-Batswana resistance to Boer aggression. During the 1852-53 war he forced Andries Pretorius to pull his subjects back to Rustenburg and Potchefstroom. Unlike the Zulu at Blood River, Sechele’s regiments were armed with guns and generally avoided charging laagers. Like Malan’s SADF, munitions were financed through ivory sales. Sechele’s arms suppliers included the veldkornet of Marico. For his part, Livingstone helped Sechele order a seven-barrelled volley gun as well as superior bullet moulds. Justifying such covert deeds to his parents, the imperialists’ myth wrote: `The only means which with the divine blessing have preserved our independence as a people are those very guns which you think the people would be better without. The tribe would have never enjoyed the gospel but for firearms. The moral suasion of their presence goes a great way with the Boers.’ — Jeff Ramsay, chairman, Kgosi Sechele I Museum, Molepolole, Botswana

Saving souls, guns or money? I WRITE this letter as a gravely concerned and ardent member of the Zion Christian Church (ZCC), who hails from the Northern Province. I will be incredibly ecstatic if these awfully worrying facts about the abovementioned religious institution could be assessed. About 60% of taxi operators or owners are displaying the emblems of the two sister religious denominations, the dove and the star, on their breast pockets, and yet they pull triggers of AK-47 assault rifles and 9mm pistols on a daily basis at the ranking facilities. Therefore the church is as much at fault as the police, for resting on its laurels when there’s considerable turmoil in the taxi industry, for not attempting to calm the waters whereas taxi carnage is repeatedly rearing its ugly head. Secondly, in contrast, it is not like its counterparts of Western origin, engaged in socio-economic upliftment projects for the pigmentally disadvantaged masses who convincingly constitute 97% of its broad-based support. Thirdly, I’m terribly confused whether this is a religious entity or financial conglomerate, hence the Lekganyane dynasty which dominated ZCC’s spiritual destiny for three-quarters of a century has acquired a considerable stake of shares in the multinational soft beverage giant Pepsi, at the expense of the hard-earned fortune of the

I’ll be more than happy if the Mail & Guardian’s prolific investigating team — according to international norms and standards — could look at this in a very serious light. — Peolwane Moshwane, Lebowakgomo

AS a supporter of gender equality I must express my dismay at the growing relationship between South Africa and Iran. So extreme is sexual apartheid in Iran that a woman literally dare not show her face on the streets — she has less freedom than a dog! I believe that, like apartheid in South Africa, this legalised cruelty can only be stopped by stringent international sanctions, and I call on the South African government to apply the strictest possible sanctions. — W Bulstrode, Parktown North

THE academic year has once again begun with the South African Students’ Congress (Sasco) attempting to blackmail Wits University into acceding to its demands or facing another year of violent protests. Despite all evidence to the contrary, Sasco has denied any allegations of violent disruptions, assaults, arson, and vandalism. There is no guarantee of safety on campus. The university’s security department is hopelessly inadequate and Sasco has had a free hand in intimidating students and damaging property. Where lies the responsibility in making non-participating students feel safe on campus? If Sasco is honest in its claim to peaceful protest, then it must focus on the administration itself and leave its fellow students alone. If the administration is still in charge of Wits, then it has an obligation to protect its students to the full extent of the law and to stop walking on political eggshells. — Darren Anthony, Orange Grove

IN response to an article by Philippa Garson and Vusi Mona (M&G January 19 to 25) concerning the magical teacher/pupil ratios of 1:40 and 1:35 for primary and high schools respectively, I would like to raise a few points: Does the Gauteng education department fully comprehend the implications of these ratios as proposed? It means that manpower will be misused to police schools which do not meet the required ratios. It could also mean that schools may have to create `ghost pupils’. This is bureaucratic failure gone mad. To reduce the problem faced by educators and all stakeholders in education to just a simple teacher/pupil ratio, particularly in `black’ schools, is very uncreative to say the least. The real problem is a high drop-out rate and the moronic wastage of resources in the former DET schools. If we talk ratios, one would have expected a goal towards a 1:20 teacher/pupil ratio as the optimum class size, evidenced by international experience. The question is how did the ministry arrive at the magic figures of 1:40 or 1:35? — Tim Dladla, Department of Economics, Vista University, East Rand Campus.

White-collar killers walk free

Date: 22 Mar 1996

Those responsible for the Merriespruit slimes dam disaster have been fined … a pittance. Bronwen Jones and Justin Pearce report

Harmony Gold Mine, found guilty of culpable homicide in the Merriespruit slimes dam disaster, is to pay a fine equivalent to one fifth of one percent of the mine’s post-tax profits for last year.

The homicide charges arise from the death of 17 people, who died when the slimes dam collapsed, sending an avalanche of mud through Merriespruit, a suburb of Virginia in the Free State goldfields, in February 1994. Six hundred people were injured, and R80-million in damage to property was recorded.

Last week the Virginia Regional Court fined Harmony R120 000 for its part in causing the mudslide. The mine’s profits for 1995 were around R56-million after tax.

Homicide charges were dropped against former mine manager Dan Jordaan, who resigned a year ago from the company, metallurgical engineer Johan Mouton, and acting plant superintendent Wayne Hatton-Jones. The three were found guilty of contravening Section 37 of the Minerals Act.

In an earlier trial, engineering company Fraser Alexander, which built the slimes dam, was fined R150 000, and further fines were imposed on employees.

An expert in construction law, Philip Loots, expressed surprise that the people found guilty were not jailed.

The fines imposed upon them were a “pittance”, says Loots, who has been examining the behaviour of Fraser Alexander and Harmony at a unique conference in Johannesburg this week.

With the ink barely dry on the Merriespruit verdicts, the spectacular slimes dam collapse entered the realm of case studies used to teach engineers how to do it better next time.

The World of Construction Disasters, a conference billed as the first of its kind in Southern Africa, revealed a sordid tale of collective stupidity, greed or weakness behind the high-cost failures of modern science — including the slimes dam disaster. In almost all cases warnings were ignored and rules broken.

Loots, author of Construction Law and Related Issues, gave a detailed assessment of the behaviour of Fraser Alexander and of Harmony in the Merriespruit incident. He explained how a slimes dam should be constructed and how the one at Merriespruit was actually made.

Loots said that Merriespurit was a dam with “high potential for harm”. “The place where a dam is situated is a factor that determines the seriousness of the consequences.”

He said it was clear in the past the state “drew no distinction between high- and low- potential harm” in its approach to safety. Building a dam and community only 300m apart is unacceptable.

“Any residential area that close to a dam would be at risk, even if it was slightly uphill,” says Loots, referring to Fraser Alexander’s proposals to build a slimes dam at Fleurhof, west of Johannesburg.

Engineering literature is stuffed full of case studies revealing the potential for danger of slimes dams, but Merriespruit had so many direct warnings it is impossible to see how the engineers ignored them. From 1992, water flowed periodically from the dam to the residential area, because it was downstream. On 11 February 1994, 12 days before the final breach, a pipeline burst and slime flowed as far as the houses.

The place where the dam wall finally collapsed had been evident as a problem area on satellite photographs since 1988. A low point had developed because of a 590m gap between “outlet stations” where, Loots says, “distances of less than 400m are preferred”.

Loots said employees also falsified pumping records after the disaster.

“They had not counted on Landsat images. We

used satellite pictures to reconstruct the truth.”

Loots explained that small slimes dams failures are regular occurrences in South Africa, but the larger ones should be used as permanent reminders of the mud’s destructive power. The Simmer & Jack failure of 1937 engulfed a train; there was another at Grootvlei in 1956, while in 1974 the Bafokeng failure produced a “mass of slime that was 800m wide and 10m deep four kilometres away from the breach”.

Loots said: “An example must be set. The fines on Harmony and Fraser Alexander were a pittance. They should be 10 times as much. Overseas there would have been jail sentences for negligence of this scale.”

There was a shocked hush when some delegates saw pictures of the devastation at Aberfan in Wales for the first time. The history of that disaster, which killed 144 people 30 years ago, was a catalogue of ignored warnings, just like Merriespruit.

Scars of the survivors

Date: 22 Mar 1996

Justin Pearce

Among the ornaments crowding every shelf in Johanna Claasens’s living room in Welkom is a mug with the inscription “Harmony Gold Mine – — 5 000 accident-free shifts”. It was given to her by a friend after Harmony’s worst accident ever — the Merriespruit mudslide in February 1994, which killed 17 people, including the 14-year-old Claasens daughter, also called Johanna.

Two years after the accident, the family’s son, Marius (13), lies on his back in the bedroom next door, encased in plaster from his chest to his thighs.

Marius was found, crushed and semi-conscious, in the mud which wiped out the family’s Merriespruit home and everything in it. The lounge suite, the flower paintings, the ruched curtains, the china dogs that now fill the small sitting room, were all acquired from scratch after the family moved to Welkom to escape the lingering fear of another disaster. “If Harmony can’t look after one of their mines how can they look after others? I saw the chance of other lives being lost.”

Last week, the Virginia Magistrate’s Court imposed fines totalling R151 000 on Harmony Gold Mine and three of its employees. “In my opinion that fine was very little,” Claasens says. “They might as well not have had the case.”

The family’s material losses, and Marius’s medical bills, have been paid by personal insurance. The family saw the R10 000 in compensation offered by Harmony as an insult: “I’ve lost a child, I must look after Marius, and they won’t reach into their pockets to help.”

The family intends bringing civil action against Harmony for compensation for their pain and suffering from the loss of their daughter and their home, and from Marius’s injuries.

At the moment she won’t put a figure on the claim, but says “one is looking for a reasonable settlement. Until Marius is fully healed, we will always have the memory that Harmony was responsible.”

Claasens’s husband Fred drives trains at another mine in Welkom; she has given up her own job with her uncle’s company to look after Marius.

Her own lost income is the least of her concerns: “I don’t think of it that way — if it’s your child, you have to do it.”

Marius spent three continuous months in hospital after the mudslide crushed the bones and internal organs of his lower body. Since then he has repeatedly gone back for further treatment. He has been immobile since his last spell in hospital two weeks ago, where shattered bones were reset, and the colostomy bag which doctors had fitted to cope with massive internal injury was removed.

He is glad to be rid of the bag, but will be bedridden for at least another five weeks before returning to school. After that, he faces another four operations, culminating in a hip replacement when he is 18. Until then, he will have to wear a built-up shoe to compensate for his legs being different lengths.

Like so many trauma survivors, Marius has blanked out all memory of the disaster and is stoically optimistic about his prospects of recovery. But he is still undergoing psychological counselling, as is his mother as she comes to terms with the loss of her daughter. He is unlikely to be very active until after the hip replacement five years hence.

In Merriespruit, 25km away, the slimes dam broods over the town like a mountain, the gap which released the fatal avalanche of mud still clearly visible. Below the gap, the mud is gone and the grass has grown again, but the path of the disaster is marked out in uprooted trees, in the foundations of houses reduced to a single layer of bricks, in the shorn-off outbuildings that were once attached to houses.

Somewhere amid this belt of destruction were the homes of two pensioner couples, Louw and Sannie Koch, and Paul and Magrieta Jerling. Sannie and Magrieta both died in the mud that swept away their houses.

All that remains of Jerling’s possessions is a Pekingese dog yapping in the garden of the new house where, aged 75, he has set up home alone.

“You know what is ironic,” says the retired shift boss as he sits in his armchair staring at the afternoon’s television programmes, a box of tissues fixed to a bracket on the wall next to him. “They say a wife is not a breadwinner. In my opinion a wife is more of a breadwinner than a husband. She was my taxi driver, my bank. I didn’t even know how to use my own bank card. I had to learn to do things myself.”

Koch, whose sombre living room is dominated by a large photo of himself and his wife, presents a courageous face, but talks frankly about his loss.

“A young man could maybe outgrow the pain. I cannot,” says Koch, who retired in 1989 from his job as Merriespruit’s fire chief.

His loneliness is exacerbated by his difficulties in holding a conversation after the toxic mud destroyed the hearing in his right ear.

Jerling and Koch agree that money cannot ease the pain of loss, but both are bitter that the law provides for financial conpensation only for breadwinners, and not for the loss of support suffered by someone who was completely dependent on a spouse.

About the fine imposed on the mining company, Koch is typically philosophical: “It makes no difference how big the fine was. If they were fined R10 or R1-million, they will carry it on their conscience for as long as they live.”

Ja, well, no fine

Date:22 Mar 1996

This is how the Virginia Regional Court apportioned fines arising from the Merriespruit slimes dam disaster:

l Harmony Gold Mine: R120 000

l Former Harmony manager Dan Jordaan: R15 000

l Harmony metallurgical engineer Johan Mouton: R8 000

l Harmony plant superintendent Wayne Hatton- Jones: R8 000

l Engineering company Fraser Alexander: R150 000

l Fraser Alexander regional manager Frikkie Botha: R30 000

l Fraser Alexander regional manager Theuns Linde: R25 000

l Foreman Adam Uys: R15 000

Botha was fired after the disaster, while both Uys and Linde are still employed at Fraser Alexander.